- Breathing Light

- Posts

- Breathing Light Issue#52

Breathing Light Issue#52

Of Small Things Writ Large

In this issue

My Image of the Week

Frontispiece

Photographer's Corner-Guest post- a photographer you have never heard of

Waiata mou te ata

Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

Endpapers

My Image of the Week

Taku mahi toi o te wiki

White Phlox | Fujifilm GFX 100, GF 100-200/4

" Happiness lies in thinking or doing that which one considers beautiful. "

Sometimes the microcosm will give us the key to the macrocosm

Someone once gave me a wonderful definition of a weed:"a weed is a plant that nobody's yet found a use for."

Not long ago I asked a friend, who is a tohunga Rongoaa (a Maaori healer who works with native plants), if she could suggest a native plant to help me with a skin condition. Was there an alternative to kawakawa growing down here, since kawakawa doesn't grow this far south? What could I use for poulticing, a traditional practice that I've been taught by another tohunga?She replied that the answer was somewhere in my garden. Walk around, she said, and look for a plant that calls to you. That was a familiar answer. Years ago, when I was travelling in South Africa, I had the good fortune to spend some time with a sangoma, the African equivalent of a tohunga. I remember him telling me the very same thing. The plants you need exist where you live. The earth which feeds you will also heal you. What they were both saying is to become aware of the mauri (essence) of each individual plant and allow it to help you.

Near here I have a wonderful friend who is also Ngāpuhi from the Hokianga. Her garden is wild and rambling, and not even remotely under control, even though she beavers away in it daily. It's one of those wonderful cottage gardens reminiscent of old England, with all manner of wonderful flowers and plants, where every corner is a new discovery.

I went to visit yesterday, and as I have the mighty Fujifilm GFX 100 Big Boy online for the holidays, I took it with me. Last year I spent a lot of time in her garden with my smaller-format cameras, following the growth cycle through spring to autumn. This time I was using a much larger camera, and, never having used it for this type of photography, I was looking for a conversation with the plants in her garden. What would it be like making insanely detailed photographs of humble things? I was itching to find out.

Even though I spent nearly 20 years in a darkroom, seeing everything tonally, one day I crossed a line and began to see everything in terms of hue. Now, unless the plant speaks the language of tones, I more conscious of the vibration of its hues, since each gives off a particular mauri. The colours are much more than a way to attract insects or birds. That particular colour energy tells you a lot about where the plant is positioned on the great matrix of the natural world.

Yesterday it was the turn of that humble herb, fennel, which is so useful in cooking, and yet is ferociously hardy, soft in appearance but tough and resilient. Just try to get rid of it once it has anchored itself to the earth! So I sat down on a chair and peered into it with my camera while, all the time, its exquisite sinuous fragrance wrapped itself around me. Somehow it drew me into its soft wonder.

When I had finished I was feeling oriented to what was happening in the garden, and went looking to see what else would talk to me. Then a proud phlox standing up alone and magnificent, called me to make its likeness.

It was recognition at first sight.And, for a small few minutes, it took off its label and showed me who it truly was, an integral part of something vast and barely comprehensible.

Frontispiece

Koorero Timatanga

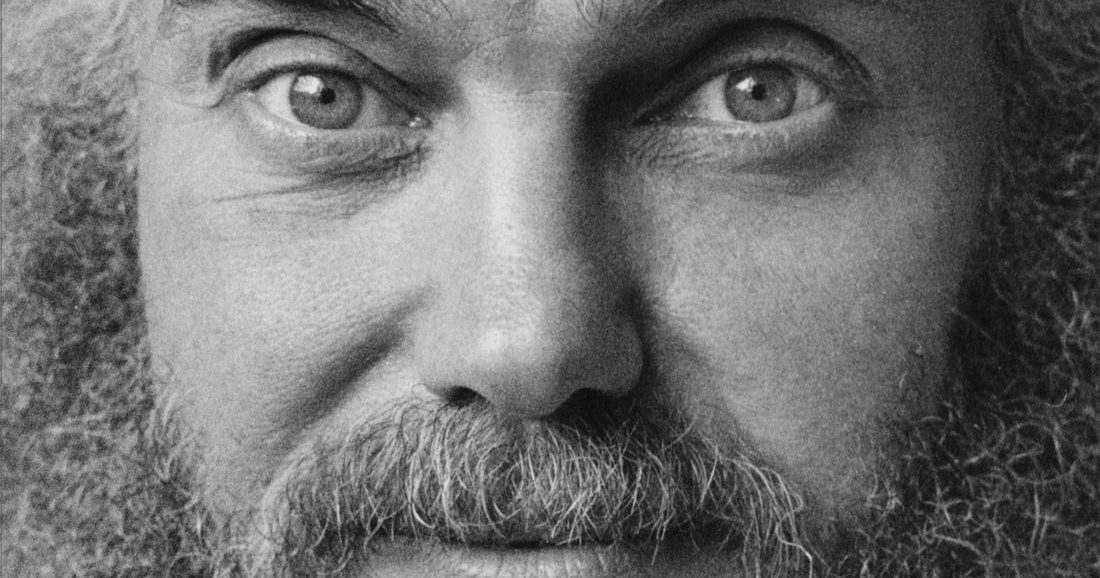

Ngaa hoa wahine o Te Raa, Rawene, Hokianga | Nikon D810, Tamron 70-200/2.8

“ Oh, what a catastrophe for man when he cut himself off from the rhythm of the year, from his unison with the sun and the earth. Oh, what a catastrophe, what a maiming of love when it was a personal, merely personal feeling, taken away from the rising and the setting of the sun and cut off from the magic connection of the solstice and the equinox! ”

Atamaarie e te whaanau:

good morning everybody.

Here you are. Issue number fifty-two. That's a year's worth of newsletters in a little over a year. Well done me (he pats himself on the back).By now, issue number fifty-two will have reached your inbox. You will either be reading it on New Year's Eve (unless you are in one of the many countries that don't celebrate New Year, in which case you won't), or you will be waking up to read it. On the other hand, if you went out and partied until four in the morning, are comatose and/or sleeping it off, you probably won't. You get the idea...

It got me thinking about the rituals we follow at this time of the year in the Western world, In particular, Christmas. All manner of comfortable myths have grown up around the ritual of Christmas, including a significant amount of commodification. Santa Claus is a case in point. The fat jolly red gentle man with his elves and reindeers, bearded, overweight and dressed in a bright red suit is, to the best of my knowledge, a marketing invention courtesy of Coca-Cola, whose trademarked red curiously matches the colour of the old boy's clothing. And Christmas as we celebrate it is a cultural overlay laid on top of a cultural overlay. According to the late mythologist, Joseph Campbell,

The night of December 25, to which date the Nativity of Christ was ultimately assigned, was exactly that of the birth of the Persian saviour Mithra, who, as an incarnation of eternal light, was born the night of the winter solstice (then dated December 25) at midnight, the instant of the turn of the year from increasing darkness to light.

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, many of us used the now-adopted Maaori phrase Meri Kirihimete, being a transliteration of Merry Christmas. Until Europeans arrived here, of course Christmas as such simply didn't exist. So what did take its place?It would probably be fair to say that Maaori would have celebrated the summer solstice, when the star Rehua (Antares) appeared over the horizon. It was also the time of Hine Raumati, one of the two wives of Te Raa, the sun god (the other was Hine Takarua). I imagine each passed the baton to the other, twice a year, at each Equinox.

Still, I cannot see Christmas as we celebrated changing anytime soon. we have too much invested in it.

Guest post

This week I'm handing over the microphone for photographer's corner to my former colleague (in a past life as a secondary school teacher) and friend, Tony Mander. You will never have heard of Tony, but is quite a master at his game. His specialty is insects, in particular insects that live on insects that live on insects. Years ago he showed me his technique for photographing them, and the clever rig he has has evolved over many years.

Photographer's Corner

Tony Mander-a master photographer you've never heard of.

A female parasitoid wasp (Palmon spp.) laying its eggs into the eggs in the egg case of a praying mantis (Orthodera novaezealandiae).

“ Nature will bear the closest inspection. She invites us to lay our eye level with her smallest leaf and take an insect view of its plain.”

Hidden away on the fringes of the photographic world other scientific photographers, whose approach is quite different to the rest of us, people like Air Force photographers, medical photographers and scientific photographers. Tony has worked for many years photographing insect life for various scientific organisations. You won't find in a book or on a website (he doesn't have one) and you definitely won't find him on social media (and his words he has no time for that). Nonetheless, his work is valuable and fascinating. I'll allow him to have the floor. Over to you, Tony.

Palmon spp. emerging

The story

This is a story of photographing an interesting insect. It also raises various issues.

But first, the story.

This is a female parasitoid wasp (Palmon spp.) laying its eggs into the eggs in the egg case of a praying mantis (Orthodera novaezealandiae). Its eggs will hatch into larvae which consume the mantid eggs and then pupate to develop into adult wasps. She is tiny, about 4mm long excluding the ovipositor.

This is an adult wasp about to emerge from the mantid egg case. The opening it occupies is about 1mm wide.

I took the egg-laying photo on 5 April 2020, the emergence photo was taken on 11 March 2021, 341 days later. Praying mantids began laying their eggs here less than 2 weeks later. The timing was exquisite, as the parasitoid females are best to arrive at an egg case before it's fully hardened otherwise they may be unable to penetrate it with their ovipositor. It also means they don't have to survive for long.

In keeping with the protocols of documentary photography post-processing was minimal.

The mystery is: how do they time when they emerge? I had kept this egg case in a sealed container on my office table directly under my bright LED table light, so it didn't have changing day-lengths or seasonal scents as timing factors. It also didn't have the seasonal range of temperatures, so a 'chemical clock' didn't seem possible as reaction rates are proportional to temperature. I also collected two other egg cases, one in December off a west-facing fence, the other in January off the east-facing side of the house. Mantid nymphs had emerged from both of these long before but there were a few spaces still to emerge, so I wondered if they were parasitised, which they were. These emerged within two days* of the one on my table, yet they had been exposed to direct sunlight, rain, snow, frost, etc. How did they know? And how could they be sure that the mantids won't lay eggs too early, or late? But they also show that all life is connected, including us: mantids in their short lifetime eat a wide range of prey, many of which also compete with us for our plant food (e.g. aphids, etc.) or can carry plant or human diseases (e.g. psyllids, flies). [*a 2-days out of 341 difference, or 0.6%, a very small variation]

Of course, when photographing little things live, Murphy’s/Sod’s Law as usual is paramount. On the day these emerged I was away most of the day, so when I checked it in the evening I was dismayed to find most had emerged (I'd waited over 11 months for this!). However, a male was waiting on the egg case, a sure sign that a female is still to emerge (female insects generally mate only once, so males need to be ready). After waiting a couple of hours this one emerged about midnight (the waiting male is in the background, and you can see the head of another about to emerge, not sure which one the male was waiting for). I was lucky to get that shot, as it sat with its head visible for about an hour, and then emerged in a few seconds—up and out very fast. I had hoped to capture it mostly out, this was an ‘insurance’ shot taken shortly before it emerged.

There are only a few hours each year when such photos can be taken, so we need to be observant and ready.

Both photos were taken in a studio situation. Is this ethical and does it affect the integrity of the photos? The emergence photo could not be taken any other way (and the natural light vs. flash argument is obviously irrelevant). The egg-laying female didn’t seem to notice that her mantid egg case and the leaf it was on had moved. Look at the miniscule depth of field, it’s nearly impossible to take that photo in the field in natural light with the usual wind blowing. (BTW, in macro at ≥1:1 the DoF spread is equal from the focus plane). I released her outside after my photos. The egg case I kept for photographing later—but I didn’t know how much later. Many years ago I had photographed a different mantid parasitoid species both egg-laying and emerging, and it had emerged in November. The adult parasitoids were released outside. While I need mantids to help control my garden pests, the parasitoids are a normal part of the local ecology. Some may ask: what use are they? All I can say is that if you ask that question you need to first ask: what use are we?

You might also ask: why take photos? For me I need to have a sense of wonder in my life and finding and recording the fascinating lives and stories of the ‘little things’ where I live helps provide that. And in finding the ‘little things’ you first have to see and appreciate the ‘bigger things’. I am also mindful of the comment by the great biologist, E. O Wilson: “Invertebrates may be the little things that run the world”. With the increasing rate of extinction of species I also wonder, with sadness, whether some of my photos may be the last time those ‘little things’ are recorded.

While these live subjects were not harmed, there are occasions when macro photos can be taken only in a studio situation, and subjects will be harmed. But that discussion is for another time.

The Process

The story of how these photos were taken.

As it is impossible to hand-hold a camera to within a fraction of a millimetre the solution was to ensure that the subject and camera shared a common mount. The camera is moved for focus, the bellows extension defines the magnification. The subject mounting can be moved precisely left-right, up/down, tilt, rotate, and means a moving subject can be kept in frame. For these photos the leaf with the mantid egg case was held in a clip in front of the camera.

I’m using Olympus OM macro lenses I’ve had for over 40 years: 38mm and 20mm focal length. These are attached to a bellows as these lenses require either extension tubes or bellows, they don’t focus to infinity. They allow me a macro range of about 1.5x to 18x magnification on the sensor. I used these lenses and a similar setup for many years with my Olympus OM film cameras and two TTL flashes. When converting to digital over 10 years ago I needed a camera where I could use these lenses, had an articulating screen, and could use TTL flashes. A Panasonic Lumix GH2 and an Olympus macro flash was the original digital setup. The photos in the article were taken with a Lumix G85. I recently rebuilt the setup again—similar but improved, and moved to an OM-1.

With subjects of only a few millimetres in size the depth of field is less than a millimetre at f/8. Why f/8? Because using f/11 or f/16 doesn’t increase the DoF very much (by just a fraction of a millimetre) but diffraction then becomes an issue (and these lenses are designed for 35mm/full frame, which generally have slightly less diffraction than m4/3 lenses).

Why flash? At higher magnifications the limitation is the effective aperture, shown by the usual formula: Effective f-stop = f-stop x (1 + Magnification), so with f/8 at (e.g.) 4x magnification the effective f stop would be f/40. This would obviously require a light intensity many of my live subjects would find very uncomfortable, plus there is always movement. Flash is unnoticed by my subjects and it freezes motion (it’s the rate of movement across the frame which counts).

While the setup looks complex in reality it means I can quickly take a photo of almost any tiny subject using the wide range of accessories I’ve made over the years. Lighting can be quickly changed from a frontal ‘main plus fill’ setup, to large diffusers, to dark-field illumination. The LED white focussing light can be switched to red LEDs which many insects find less intrusive. As most of what I do is documentary photography I quite often use a grey card as a background, useful for exposure and colour checking.

Waiata mou te ata-poem for the morning

Earthing Earthling Earthsong

Golden Chamomile | Fujifilm GFX 100, GF 100-200/4

“A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

Earthing Earthling Earthsong

In the half-light purple echo of the dark,

before the sun strips away

the shadowhorned glumgloom quilt of night,

and casts it daily to one side

eye rise iriswide aware and open to receive.

I stumble outside,

hope in hand,

to root my soul and soles

in murmuring leaves of grass

with stories to shear

from the half-moons ticktock pendulum sway away

across the underbelly of the night.

Somewhere above me (and to the right)

among the roughly charcoaled pencilpines,

a bellbird drips a single fragrant note,

casting it out and away

into a widening well of rising light.

Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

End Papers

Koorero Whakamutunga

Stairwell and Wild Garden | Fujifilm GFX 100, GF 45-100/4

" Maybe Christmas, the Grinch thought, doesn't come from a store."

On New Year's resolutions

It is customary at this time of the year for people to ask each other:"so what are your New Year's resolutions going to be? What are you going to do better (give up) in the coming year?"

I try to slip away as quickly as possible, mumbling that I'm thinking about…Do you do the same?However, this year, I've decided it's time to really up my reo game, and build on what little I know. And I found a way that really helps.This year, as my Christmas present to myself, I ordered a new diary from the wonderful people at Tuhi stationery (see the link below), who produce a truly beautiful diary, full of karakia, whakatauki and kiiwaha (sayings), along with days of the week and months, including the lunar calendar. It's a very lovely production, and it offers opportunities to reflect upon your own journey. My aim is to get to the other end of the year having used it daily (knowing me, it will be almost daily). It really is quite exquisite, more of a taonga (treasure) then a boring diary. I'm thinking I'll go and find my fountain pen so, when I have something to write down, I can watch the miracle of ink flowing onto paper and then drying.

On conundrums and choices

The other night I wandered out into the lounge and for whatever reason, picked up my wallet. Lurking underneath was a rather large whitetail spider. My immediate reaction was to pick up something heavy and convert her into the new flattened model whitetail spider.Then I thought about it. And watched her sitting there, moving his legs and eyeing me.As I saw it, I had three choices.

-Squash her flat. Somehow that didn't feel right.

-Put her outside, knowing that she would probably come straight back inside.

-Send him on his way courtesy of the toilet, knowing that he would probably find a way out somewhere.

I chose the last option.

Next morning I was sitting outside when a small spider (hopefully not one of her offspring) meandered along my leg. It was barely 3 mm long and, rather than harm it, I brushed it lightly off me and watched it amble away across the patio.

Lately I've been thinking about the relationship I have with the natural world. It hasn't helped reading a wonderful book Sacred Nature by Karen Armstrong (I have supplied a link below for any of you who might want to follow it), which asks each of us to see ourselves as an integral part of something much bigger and more sacred, as an integral part of an incredible eco-sphere, where everything has consciousness and its own consciousness. Can we harm a fly? I am not so sure about that. Flies after all have their place in the natural world. If we begin to see ourselves as no more or less important than any other creature, then it brings us a range of responsibilities and obligations that we might not have considered or indeed wish to consider.

I once visited a stupa in South Africa and talked to the people who own the property where it was situated. They told me how Buddhist monks had come all the way from Tibet to build it and before they would put any earth and/or sand into the structure, they would carefully sieve it and remove any insects they found, placing them safely to one side. A true reverence for the natural world.

Imagine if we all made it our New Years resolution to improve our relationship with and guardianship of the natural world from which we came, which feeds us, and ultimately to which we will return?

As always,

Please keep safe and be kind to each other.

He mihi arohaa nunui ki a koutou katoa

Much love to you all

Reply