Flagstaff at Dawn, Waitangi Treaty Grounds 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

1.Koorero Timatanga-Frontispiece

2. Waitangi Day 2024-A hikoi

2. Letters to my Friends-Letter to Jeremy Pt. II: On the principle of moments

4. Waiata mou te Ata-Poem for the day

5. Nine or Ten Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

6. Koorero Whakamutunga-Endpapers

Frontispiece

Koorero Timatanga

The hikoi arrives at Waitangi, 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

“Color is very much about atmosphere and emotion and the feel of a place.”

Atamaarie e te whaanau:

Good morning, everybody,

There is a beautiful whakatauki (maaori proverb), often quoted and shared.

Hutia te rito o te harakeke, kei hea te komako e ko?

If you pull out the centre shoot of the flax plant, where will the bellbird sing?

Ki te uia mai koe, he aha te mea nui o te ao?

If you ask me, what is the most important thing in the world?

Maku e kii atu, he tangata, he tangata, he tangata.

I will tell you, it is people, it is people, it is people.

Like all whakatauki, it is expressed as a metaphor, and unpacking the meaning can be tricky unless you know the right person to talk to.

When you look at the harakeke, a flax plant, there are three shoots. The middle represents the child, and the larger ones on either side represent its parents. If you cut the two outer shoots, the middle one will not grow. The metaphor is obvious. Children, our future, require two parents to raise them into adulthood. All kairaranga (Maaori Weavers) know this. The other part of the whakatauki points out that it is people on whom we must focus. We are, after all, on a waka (canoe), sharing a common human journey. We cannot be human without paying attention and notice to those around us.

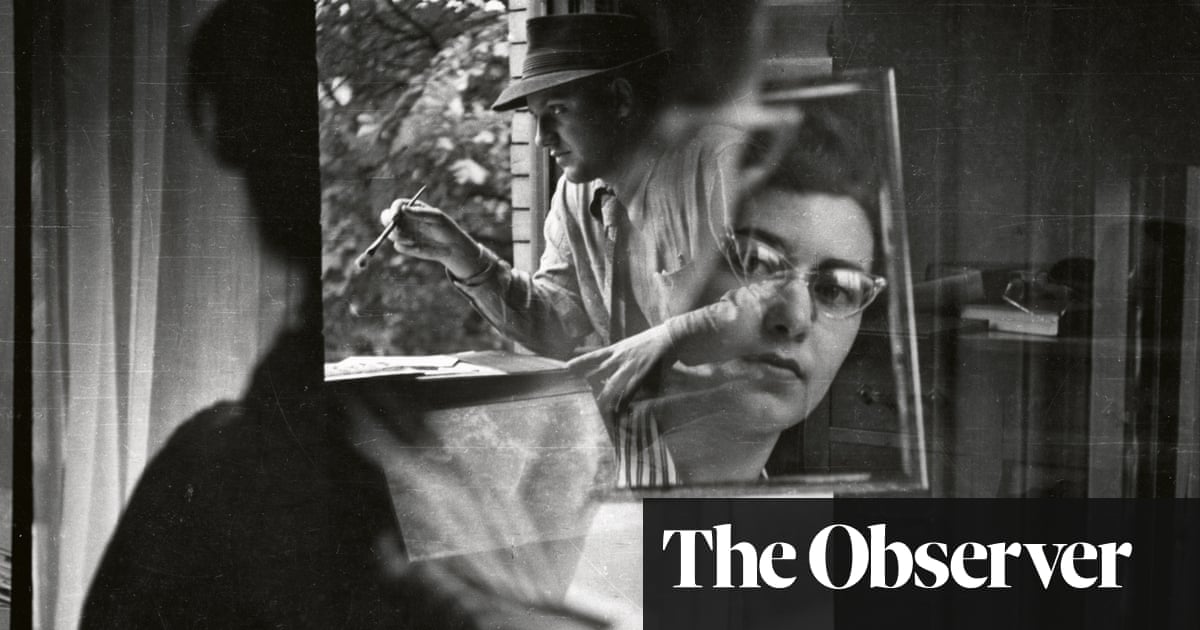

It is been a while since I was prolific with Breathing Light (you may have noticed!). For a long time, my focus has been on the Taiao, the natural world, either writ large or writ small. However, for some time, I have felt that I am moving on (or perhaps moving backwards) to another place and time in a new working style.

Each time I put out Breathing Light, I attempt to create new works to support the koorero (text). You may have noticed that occasionally, I dipped into my archives, bringing up work from as far ago as 20 years ago. However, having been here in Te Tai Tokerau (the Far North of Aotea Roa/New Zealand), I have been at a loss regarding what I need to say about the land.

It has not helped that, despite Fujifilm New Zealand’s generosity, I have been relatively camera-free for the last 18 months.

Then, the stars have begun to align in the last couple of months.

I realised that it was time to begin rebuilding my camera kit. Frankly, a phone does not cut it!

Being a Fuji boy, I am addicted to the images they can produce.

Fujifilm New Zealand buys demonstrator cameras, which they loan out to X —photographers ( brand ambassadors like myself or two people thinking of making the (very wise) decision to dump their Canon or Nikon cameras and go Fuji. Of course, as the models are replaced with new and better versions, the old ones languish unloved and unused in the back of the demonstrator cupboard. This is not to say they have suddenly become useless- far from that, simply no one is interested anymore in a model that may be up to 2 generations old. So, I asked if they would let me have the X-Pro 2, their best camera for documentary and street photographers. The lens they supplied is also now a generation old and consequently unloved, but still a fabulous piece of glass.

Do you think I could have it to photograph Waitangi Day? I asked.

Of course.

Last year, the country elected a right-wing coalition government, including a minority party with a more prominent voice than it deserves, which is determined to destroy or alter the founding documents of our nation and makes a lot of noise trying to achieve that goal.

Let me clarify.

In 1840, the Crown (Queen Victoria’s English government) signed a treaty with Maaori, the indigenous people of Aotea Roa, in which the government agreed to protect the Maaori people and maintain their sovereignty over their affairs. Of course, as European colonial governments do, they broke the spirit and letter of the agreement. Maaori, who never ceded sovereignty or conceded defeat, have been on the back foot ever since.

When the right-wing government, late last year, began making moves about further disempowering Maaori, the proverbial hit the fan. We Maaori are a nation of warriors and do not back down.

I had never been to Waitangi on Waitangi Day, the national celebration of our founding document, Te Tiririti O Waitangi, and this year, I was determined to go.

The MSM devote a lot of time, energy and vitriol to the politics of the day at Waitangi, where we celebrate ourselves as a nation and our kotahitanga (interracial unity). People I talked to were nervous about going. In previous years, politicians have been derided (one was even hit with a dildo). Yet, stories I heard said that the four-day event was joyous, with people laughing and smiling and sharing, and that to be at Waitangi was a significant and lovely event.

So, Dear Reader, this is a Breathing Light, where I have changed gears from my journey as a landscape nature photographer to my great joy as a documentary/street photographer. I want to share the memories of that day, and I look forward to your feedback.

Please keep one Maaori word in mind:

Hikoi

it means journeying with a purpose and for a reason.

My reason was to go to Waitangi and see the joy and wonder of human beings from all races coming together with a common purpose.

Ngaa mihi nunui aroha ki a koe.

Much love to you.

Flagstaff at Waitangi, 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

Waitangi Day 2024

A hikoi

Dawn, Waitangi, 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

“I think photojournalism is documentary photography with a purpose.”

He hikoi ki Waitangi

A journey to Waitangi

It is 3:45 in the morning. Like paua (abalone), we have prised ourselves from the rock of our bed, determined to get to Waitangi well before dawn and participate in the predawn ceremony. We know it will be full of important people and politicians, yet the day will be nothing without the people who come.

And come we do. In thousands.

We are stuck in traffic on a winding back road to Waitangi (I did not know it existed!). On a dusty gravel road, we inch forward, following a line of cars that stretch ahead of us and up over a hole. Frankly, we have no idea where we are, but we trust the process that we will get there. Because there are so many others in front of and behind us, we know we are on the right path-whatever that is. The conga line of headlights and taillights inches its way slowly along.

Eventually, we find a park amongst hordes of other cars, and we stumble across the grass in the dark to the shuttle buses that will take us down to the treaty grounds and the upper marae. Do we have everything we need for the day? The buses fill up, and abruptly, we are off. None of us know where we are going, but the cheery greetings and banter of the driver convince us he has it all under control.

After five minutes or so, we disembark and stumble through the darkness to the Upper Treaty Grounds, where the Very Important People are doing whatever they do. Because we are late and because we are unimportant, we find a place to sit and watch the ceremony from a distance. The darkness is a korowai (cloak) that unfolds us. Nearby are two container café’s, with queues at least 50 yards long, making coffee as quickly as they can. Ah! The Kiwi's addiction to coffee!

For reasons I cannot fathom, I am overwhelmed by emotion, with tears pouring down my face. Something profound is going on within me. Perhaps I will never know what it is.

As we sit on a park bench at the back, we begin to meet the people who have come to be at Waitangi. We encounter Clint, whose family have lived in Waima, in Hokianga forever. Clint has diabetes and cannot sit down for very long. When he needs to sit, one of us will stand up for him. Clint is living in Whangaarei, and because he has little or no money (he is doing his best on the benefit), he has hitchhiked up to be here for the day. He tells us with a bit of awe in his voice that his last pickup was driving a Tesla.

“I have never been in a Tesla before,” he says breathlessly. I say a big mihi (a sign of respect) to the Tesla driver for stopping and helping someone on the ladder's bottom rungs.

There are good buggers.

And so it continues. Conversation follows conversation. Because it is a national day of unity, people are talking to each other, sharing their life journeys and experiences, and the joy of being present on a national day of unity.

Then the sun rises.

Ka whiti te raa, it is day.

Away to the east, over the hills, the sun creeps relentlessly above the horizon. The sudden burst of warm, golden light illuminates the Flagstaff and people milling around it. It is both profound and moving.

Kotahitanga. Unity.

We are one.

We meet John Campbell, New Zealand’s leading journalist, and it is a joyous encounter. He is even more humble and gracious than he appears on television. I become an instant fan of a man who does so much good in a troubled world.

Later, after coffee at the hotel and rubbing shoulders with politicians and journalists, we make our way down to the bridge across the river to the Lower Treaty Grounds. The war canoes are on the water, including the legendary Ngātokimatawhaorua, with its many paddlers. Other waka join them as they make their way to enact the landing. On the bridge, swarming harmonies of people are waiting to see and photograph. Many of them are clad in Te Kara (the flag of the United Tribes from 1835 and the Declaration of Independence), along with the Tinorangatiratanga flag, which celebrates Maaori sovereignty and self-determination.

I wander among the many stalls and meet a tohunga ( Maaori shaman), who has developed his own kura puurakau (martial arts school with traditional Maaori weapons). He is holding a demonstration day (perhaps looking for more akonga/students). We talk for a time. He explains to me his philosophy about oneness and centring the body, and, in doing so, I am gifted maatauranga tapu (sacred knowledge) about how to align the body to the sacred energies.

Kura Pūrakau, Waitangi 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

I return to where our stuff is sitting on a bench. Nobody has bothered to interfere with it or even steal it. It is that kind of day.

Then, a buzz begins to build among the crowd.

People, a lot of people, are marching up the road towards the Upper Treaty Grounds. It is the arrival of a hikoi, which has been marching for some days. The press will paint it as a mere 600 people. I estimate they are in their thousands, people concerned at the deletion or alteration of our founding document and the statement of who we are. Obviously Maaori are represented, but the ranks are heavy with tangata tiriti, paakehaa/ European people. The crowd is friendly, welcoming and focused. Over the next 30 minutes, they snake across the bridge, ten people deep, people from all walks of life and all age groups making their way to the upper treaty grounds.

When I speak to people who have been here before, they cannot get over the vastness of the crowd. It is as if people have been energised to turn up and make a stand. However, the mood is peaceful, friendly and warm, with none of the argy-bargy of previous years as expected by the MSM.

People coming together to share and celebrate.

After finding a stall selling food, we begin returning towards the Upper Treaty Grounds. By now, the midday heat is flattening people and squashing them into overheated submission. We are all looking for places with shade to rest and take stock.

On our way back, we pass a marquee with a performance about to begin. On the whaariki ( mats) laid on the grass are a number of small children about to start a performance. They range in age from 7 to 12. Their kaiako (teacher) explains that less than two years before, they did not know their own culture. Now, they are fluent in their language and culture. They perform haka and waiata proudly. Their mana (presence ) is glowing and shining from their faces. Again, my tears come. If these rangatahi ( young ones) are the future, then there is hope for us.

As seniors, we take advantage of the golf carts that travel up and down the road, helping older people make their way back up the hill. Well, why wouldn't we?

Like all events of this nature, people write their own scripts for the day and come to enact them as best they can. As a photographer and observer, I am interested in finding those points of intersection where one person's script interacts with another’s.

By 1330, the wind has begun to rise and peel some of the heat from the day. We spend time watching the concerts, and then it is time to go. People are beginning to fade, and many have already left.

We join a long queue of people grilling in the sun while waiting for the shuttle buses to take them back up the hill to their cars. Us included. However, while the crowd is a little tired and snappy, the bus drivers are warm, friendly, and helpful.

We return to our car and make our way home.

I wonder about the people who made a solid attempt to get here, how the rest of the day went for them and what will be involved in them making their way home. Some of them have come from as far away as Southland, Canterbury and Wellington, determined to take part in a national day of unity and celebration.

I know that this has been the most significant and most profound of the Waitangi Day celebrations. Or so I am told.

Will I come again?

I do not know.

However, the experience and the memory will stay with me for the rest of my days.

Photographer's Corner

Letters to My Friends

Letter to Jeremy Pt II:

On the principle of moments

Waitangi Day, 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

“The flow of people in a setting, their changing relationships to each other and their environment, and their constantly changing expressions and movements - all combine to create dynamic situations that provide the photographer with limitless choices of when to push the button. By choosing a precise intersection between subject and time, he may transform the ordinary into the extraordinary and the real into the surreal.”

Dear Jeremy:

We have talked often about documentary photography and how to go about it.

I would love to talk to you about the three documentary photography styles and how we can move between them, depending on our intention and what we are trying to say.

The first style (and not the first) is as Confrontational. Here, we confront our subjects directly, interacting with them, and they interact with us. Our subject is looking directly into the camera, and we learn about them from their reaction to us. We place them in time and space, so one of the key things to master here is being aware of where they are and their relation to their location/background, which helps us learn more about them and their place in the world. Finding the balance between subject and environment is a crucial subject to master. We need to ensure that what is around them contributes to our understanding of them so a future reader can use the background to help understand them. Too much around them will be a story about the background with the person included, while over-representing them in the frame will contribute very little and be, in effect, a portrait. The great documentary photographer Gary Winograd was exploring this relationship not long before he died. Studying his work may well help you to get a better sense of how to balance your picture-making.

The second style is Observed. Here, the photographer takes a fly-on-the-wall approach. He watches, observes, and documents. Perhaps he intends to record time and space and moment. He will, of necessity, pay attention to the particular movement of people. He may see some lovely synchronicities or juxtapositions of subjects that create a new story. The Magnum photographers Alex Webb and Constantin Manos are masters of this type of photography. They produce pictures beyond mere statements of time and place and offer insights into the human condition. I recommend you check them out. Study their photographs, note the material within the frame, and how they often allude to something well beyond a simple document time and place. There may be inferences drawn about the human condition or the strangeness of life. Photographers who work in this style are, of necessity, people watchers, people who will sit for hours at a street café, watching passers-by and attempting to create photographs that talk about the human condition.

The third style is Random. In the style of photography, the photographer cedes control to chance. He lets go of any form of pre-determination and technical control. He allows himself to be dictated to by moment and opportunity. There is no attempt to control what comes to the camera. One way of doing this is to allow the camera to do the work, to move in the scene, press the shutter when it feels right, and review what happens later. He may well ignore his viewfinder, the tyranny of framing, and allow what will come to come. By letting go, he is open to moment and chance. If you try this approach, you may be surprised by what you get. It is a very effective way to work a crowd or something that is changing rapidly. In many ways, it is about having faith in yourself and your ability to respond.

The great photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is (falsely) credited with the phrase “decisive moment”. In his book The Mind’s Eye, he discusses the philosophy of his approach. It is worth a read. I think most great documentary photographers are well aware of this.

While working on my project photographing the nightclub scene on Oxford Terrace in Christchurch in the early 2000s, I often sat on a bench, watching people go by. From a seated position, getting a sense of time and place was challenging when I was lower than the people passing by. All I could see were passing legs and lower torsos. Because of this, I began to focus on the movement of their legs and feet. I would make pictures of legs and feet. When a person is walking, there is a point when the foot is neither on the ground (static) nor in the air (mobile) but somewhere between. I began to look for synchronicities between different people’s feet.

I began to understand that at times like this, everybody present had arrived, having written their own script for what they wanted to happen. Once present on-scene, they attempted to enact it. Of course, everybody else present also had their own version, and it was at the intersection of those scripts, truth would often be found. I began to be fascinated by these energy lines of intention, how they interacted, overlapped, and, in some cases, repelled each other. Opposites attract, and like repels like. Rather like a magnet, really.

In the header image for the section, I was sitting on a bench in the shade at Waitangi. I began focusing on the legs and feet. If you look closer at the picture (I am happy to supply a larger version if needed), you can see synchronicity between foot movements. While it is not a picture of Waitangi Day per se, to my mind, it represents the to-and-froing that occurs when people are moving in a space.

In his seminal book The Five Rings, the great Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi talks about being in the Void when you fight. In other words, he means being in a space where you do not think; you are. As a martial artist, I know you will understand this concept. Bruce Lee, one of the great martial artists, had this to say:

“if you have to think, you are dead.”

Both understood the importance of getting your mind out of the way.

Mind is way too slow.

And perhaps that is the art of documentary photography.

It is being in the Void when you photograph.

If you have any questions you would like me to answer, please drop me a line and let me know what they are.

The hikoi arrives at Waitangi | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

Waiata Mou Te Ata-Poem For the Day

Signs and Intersection, Waitangi 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

“Culture makes people understand each other better. And if they understand each other better in their soul, it is easier to overcome the economic and political barriers. But first they have to understand that their neighbour is, in the end, just like them, with the same problems, the same questions.”

I was contemplating which piece of poetry would best fit this edition of Breathing Light and integrate it into a narrative about Waitangi Day.

One of the things about living up here is the sense of history and the layers of human experience you can find all around. So I reached back for a poem from my book Raahui, which I wrote in 2020 during lockdown. On each of the 30 days we were confined to quarters, I would get up, create a piece of poetry and then share it. Eventually, it found its way into the form of a published book, which sold out very quickly.

I imagined what it must have been like for my Maaori ancestors when the first tall ships sailed into the North. I imagined myself standing on the cliff top, staring in wonder at a boat that I had never seen before. Perhaps some of my ancestors had a sense of foreboding that things would never be the same again.

And they have not.

Immigrant song

On day twenty

A rough profanity of sailors

Speaking in an angular-edged foreign tongue

Staggered drunkenly in across the night,

Cutting apart the soft sliding slurp

of the slithering sleeping bay,

and drew us whispering down

from the green-feathered crown

of our sacred, soft-dreaming mountain,

to watch in grim-jawed fascination

as an alien future drew ever near,

(an uninvited guest)

In puffed-up towers

of shadowy, shuddering white

And creaking black-iron self-importance.

Nine or Ten Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

EndPapers

Koorero Whakamutunga

Near the Lower Treaty Grounds, Waitangi Day, 2024 | Fujifilm X-Pro 2, XF 10-24/4

"If we are to achieve a richer culture, rich in contrasting values, we must recognize the whole gamut of human potentialities, and so weave a less arbitrary social fabric, one in which each diverse human gift will find a fitting place."

And there you have it.

I am very aware that many of you are reading this from different parts of the planet. Because you are not Kiwis, you probably have little or no understanding of the cultural riporipo (whirlpools) that are currently swirling in our country.

Waitangi Day, which was once honoured more in the breach than the observance, has suddenly taken on a greater significance as right-wing forces attempt to dismantle what has stood for nearly 200 years as a rock upon which our nation was founded in an attempt to create a state of peaceful coexistence. When the treaty was signed in 1840, European settlers were vastly outnumbered by Maaori. I would like to believe that, at the time, intentions on both sides were good and that there was no Machiavellian intention on the part of the British colonisers. However, not being there, I am not so sure. The document signed was in both English and te reo Māori. However, The Maaori version differs from the English one in terms of language and cultural understanding.

And, as people do, intention and meaning have been warped to suit individual agendas.

My intention in writing this issue of Breathing Light was to show that people are people, cultural differences or not and that the power of being human lies in our ability to organise and work together. When we do that, we are like the Roman fasces, the collection of sticks which, when joined together, is unbreakable. The metaphor is obvious.

It also reminded me of a saying I heard in Africa:

“What is the slowest thing on legs in Africa?”

“Man.”

May the coming week bring you love, strength, insight, truth and peace, the only things we may ask of our Creator.

As always, let us walk gently upon our Mother and be kind to each other.

He mihi arohaa nunui ki a koutou.

Much love to you all,

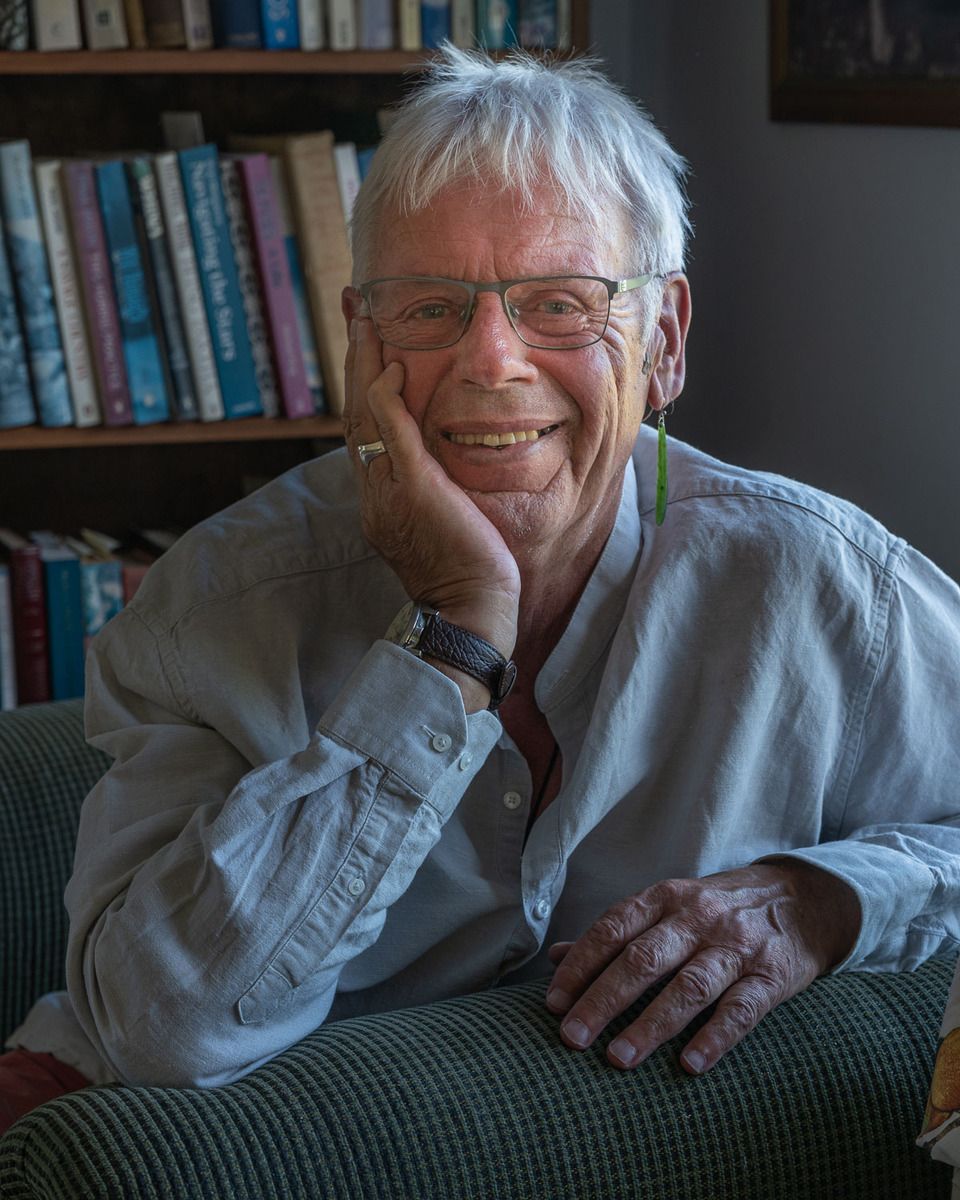

Tony/Te Kupenga a Taramainuku

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/6BHEGHKERPMUQVDUD6CFI5F2AA.jpg)