In this Issue

1. Taku Mahi Toi o Te wiki-My Artwork of the Week

2. Korero Timatanga-Frontispiece

3. Letters to my Friends-Letter to Charlie: On Falling into the Space Between Projects

4. Waiata mou te Ata-Poem for the day

5. Nine or Ten Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

6. Koorero Whakamutunga-Endpapers

My Artwork of the Week

Taku Mahi Toi o Te Wiki

Coal River, Fiordland 2018 | Fujifilm X-H1, EF16-55/2.8

"There is pleasure in the pathless woods, there is rapture in the lonely shore, there is society where none intrudes, by the deep sea, and music in its roar; I love not Man the less, but Nature more."

Somewhere on the bottom south-west corner of the UNESCO World Heritage Park of Fiordland is a small bay named Coal River. It is rarely, if ever, visited, and there is a reason for that. There is no way to reach it on foot. It is simply impossible. The other alternatives involve a bumpy ride by boat on a sea filled with potholes and a problematic landing, probably in a Zodiac since there is no mooring for a vessel of any size.

The other way is to fly in by helicopter, an expensive journey indeed. The local helicopter pilots are very protective of it and may turn down a request. There is a reason for this.

Coal River is one of the most unspoiled parts of the park. You will see deer footprints littering the black sands as you wander around. The forest is rough, raw and unmodified. In addition to this, the Bay will bear the full brunt of a north-west storm crossing the Tasman. Even the dunes, which have almost no human footprints, have a rugged sense of being untouched and unspoiled.

However, the wonder of this place lies in its vast mats of pingao, a native sedge, once prevalent in dunes right across Aotea Roa but increasingly threatened by farming and human presence. It is highly valued by kairaranga and Maaori weavers and is only used for significant things, like the bindings on tukutuku panels in a wharenui (Maaori meeting house). Of course, wild animals will not eat it since there are better things for them to eat, requiring less digestion.

We had been flying throughout Fiordland, photographing the fjords and lakes for Ngāi Tahu, the iwi (tribe) responsible for Te Wai Pounamu, the country's South Island. They had commissioned me to fly the entire length of the West Coast, documenting places of significance and importance to them. In many every way, it was a dream job.

Kim, our pilot, had a smile on his face.

“I really want to take you to Coal River. It is probably my favourite place in Fiordland.” Kim, in his early 60s, has been flying in the area since he was a teenager.

We slithered into the Bay, and he put the helicopter down softly on black sands.

“Be warned; this place is the namu (native sandfly) capital of the world.”

He was correct. Even though we landed in the middle of winter, these nasty little insects came out to attack us, descending on us in squadrons. I thought to myself, God knows what they must be like in summer when the weather is warm. I resolved never to have to find out.

Then, as we wandered around, I became very aware of the pingao, a native sedge, once prevalent throughout the country but now hard to find. I had never seen so much of it in one place. It rambled and wandered gaily over the dunes, waving its tousled and spiky hair in the soft wind blowing in from the sea. There was no contractual requirement to photograph it, but why wouldn't I? I had no idea if I would ever come this way again.

At first, the pingao was a dull gold, and then something extraordinary happened. The glowering clouds and threatening rain pulled back, and the sun flowed a pool of light onto the patch which had my attention. Off to my right, a rainbow appeared briefly. I took this as a tohu (sign/portent) that the atua (gods) approved of what I was doing.

Kim asked for a copy when he saw it, so I printed two in A1 size for him and his friend Greg.

I also promised that provided he framed it correctly, I would never print it in that size again.

However, I will release a limited edition of only five prints in A2 size. I will print those myself to order.

Larger sizes are NOT available on request.

Limited Edition A2 only

$NZ 1000 (print only).

Frontispiece

Koorero Timatanga

Towards Uenuku, Paatea / Doubtful Sound, 2018 | Fujifilm X-H1, EF16-55/2.8

“A person however learned and qualified in his life's work in whom gratitude is absent, is devoid of that beauty of character which makes personality fragrant.”

Atamaarie e te whaanau:

Good morning, everybody,

Each week, when thinking about what to write in Breathing Light, I look for a thread to bind the issue together thematically.

This week is devoted to Fiordland, whose border I have lived on for the last five years. I came down here five years ago on a commission to photograph it, and somehow, I have never left. It has entranced me and held me under its spell for the last half-decade.

Fiordland is a vast, largely untouched wilderness of more than 1.2 million hectares punctuated by lakes and 14 fjords, each unique. Right now, where I live, Te Anau is seething with tourists, with buses large and small, swarms of camper vans and tiny Toyota Corollas, all filled with people eager to experience Fiordland. Each morning, the tour buses trundle out of town, taking people to Patea Doubtful Sound or the more popular Piopiotahi Milford Sound. A lot of bucket lists are being ticked at the moment.

However, since there are only two roads into the National Park and one Great Walk (the Milford Track, which, when bookings open, fills up for the season in less than five minutes). It isn't easy to appreciate Fiordland's immensity and wonder unless you fly over it. The best way is to book a helicopter, which some people do; however, they are expensive to run and more expensive to charter. For that reason, 99% of tourists only ever see the periphery.

When I came down in 2018, I never thought I would settle here and make Fiordland's extraordinary energy the subject of my picture-making. And yet here we are.

This week's issue, #80, contains pictures that are especially dear to me. I first became aware of the raw, pure energy in the land while flying over it. One day, as we were flying back to Te Anau, I looked over my shoulder and saw the wairua (spirit) of the place, with multiple whiri (threads) of energy binding the landscape together. When it came time to build my new website, the image as the header of this section was the logical choice.

In many ways, my kaupapa (mission) here as an artist has been documenting that to make the invisible visible.

However, is that not what artists do?

Photographer's Corner

Letters to My Friends

Letter to Charlie:

On Falling into the Space Between Projects

Somewhere in Fiordland, 2018 | Fujifilm X-H1, EF16-55/2.8

"The sun, with all those planets revolving around it and dependent on it, can still ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do."

Letters to My Friends

Letter to Charlie:

On Falling into the Space Between Projects

Dear Charlie:

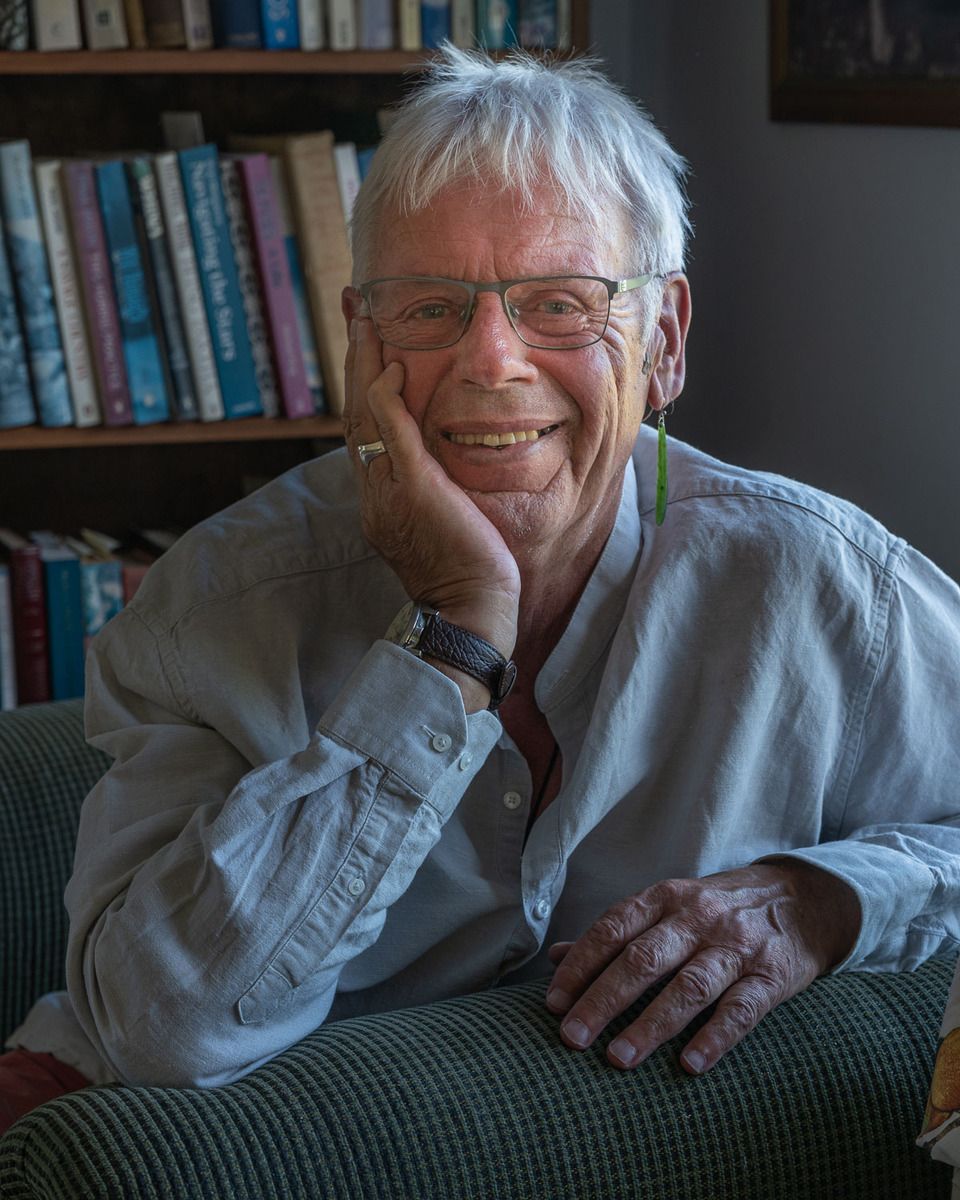

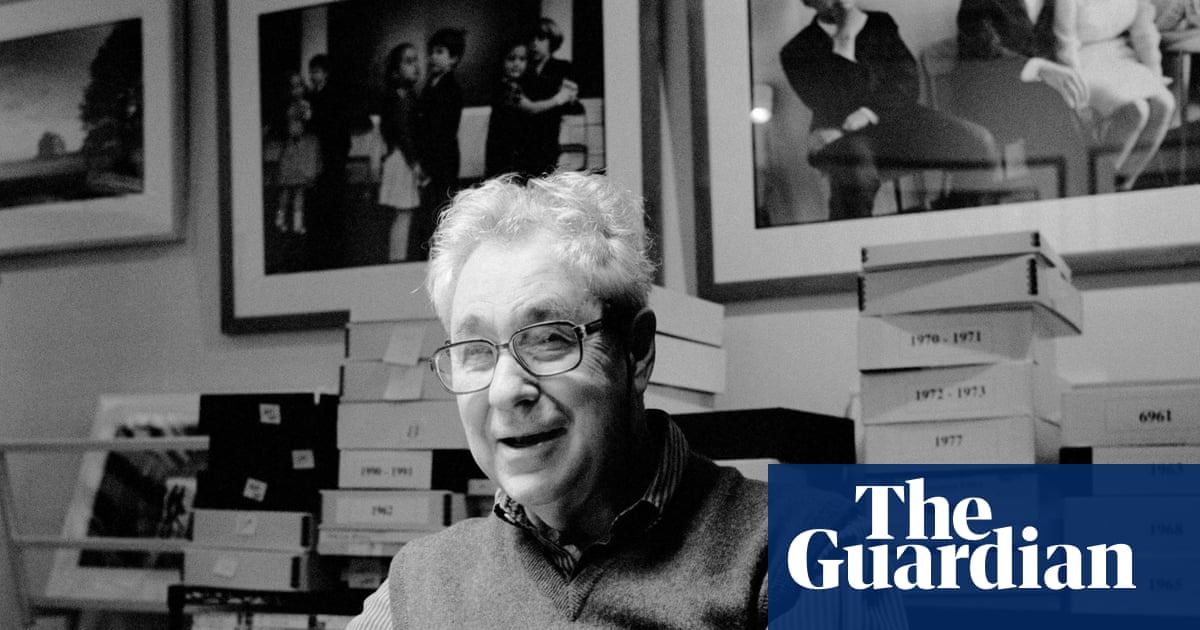

Walking alongside you for the last year and a half has been an absolute joy. One of the things I love about my work as a mentor is sharing all the knowledge locked up inside me from 40 years of walking the road and picking those things from inside the Bridge Library that relate to the journey you are trying to make.

What is even lovelier is that we have gone from a mentor-mentoree relationship to being simply friends, able to sit and chat on opposite sides of the planet and share our thoughts and ideas. I am not sure who said it, but there is a lot of truth to be found in the thought that the best day is when the student surpasses the teacher.

When we were talking online a couple of weeks ago, you told me how your long photographic journey with the woods near your home is ending and that your book is beginning to shape itself into something concrete. It will not be long before your work will be present in a tangible form. There is great joy in coming to the end of an artistic journey, of knowing that you have done all you could. Now, it is a case of shaping it into something extraordinary, which will be a legacy for your family and a wonder to be treasured by all the people who buy it. Never forget that even though you have reached a particular milestone, there will be those on the road behind you who will look to your example for inspiration and encouragement.

This is a perfectly natural process. When we move from opportunistic photography, seeking a picture here or there was no framework around it other than the pure joy of making a picture of this or that, hoping for likes and approval, whether it be within a club or on social media, we begin to follow the artist's road, of following an idea and building a body of work around it. When we move into this space, we are chasing an answer to a question. We begin with the question and then start to explore our response to it bit by bit, building up a collection of responses. As time progresses, we begin to discern patterns and directions that we can modify as needed. It can be a joyous thing to follow that pathway through the woods (pun intended!), And find where it leads. It feels to me that most artistic endeavour follows that path and process.

However, if we are wise, we will realise when we have nothing left to say, when we have been down all the side roads and cul-de-sacs on our journey. Then it is time, if we are wise and sensitive to it, to let go and move on.

I think the great artist David Hockney is correct when he points out that all art is about solving problems, then having answered them to our own satisfaction, and being willing to let go and move on to the next one.

However, that can be a difficult time. Somehow, we have moved from a direction through the forest to standing without a sense of where to go next. If we have been focused on following a particular journey, finding ourselves out in the open plains without signposts can make us uneasy and uncomfortable.

Rest assured that if we are committed to our journey, the next question will come, and we will be on a new path through a different forest.

I love that beautiful poem by the great American poet Robert Frost, Stopping By Woods On A Snowy Evening, where he talks about riding his horse through a winter forest in the snow. You may know it. I particularly love the last verse:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

It has always struck me that there is a lot of truth to that. In many ways, as artists, we have promises to keep (to ourselves) and miles to go before we are done.

However, that sense of being between projects (your words) can be uncomfortable and somewhat challenging.

I know my work has periodically shifted, usually in blocks of 3 to 5 years. Suddenly it dawns on me that I am repeating myself and recycling ideas past their use-by date. Suddenly, I find myself uninterested in picking up my camera because I have nothing more to say. That happened to me in the Maniototo, so my journey took me north to Hokianga, where my work shifted radically. Three years later, it happened again when I found myself repeating myself once more.

It was time to move on.

When I was travelling south to work on my Fiordland commission, I was worried that my work would repeat the grand landscapes of my time in Central Otago.

I need not have worried. While I would move back to the grandeur and wonder of the South, my work found an entirely new expression that fascinated me.

That was five years ago. I moved from the power and energy of the grand landscape to the world written small (i.e., plants) and focused on that.

Lately, however, I have found the world of plants no longer holds the challenge it once did and that I am between projects.

Once, I would have fretted. I am content to explore, think, and wait to see what happens.

What will the next question be?

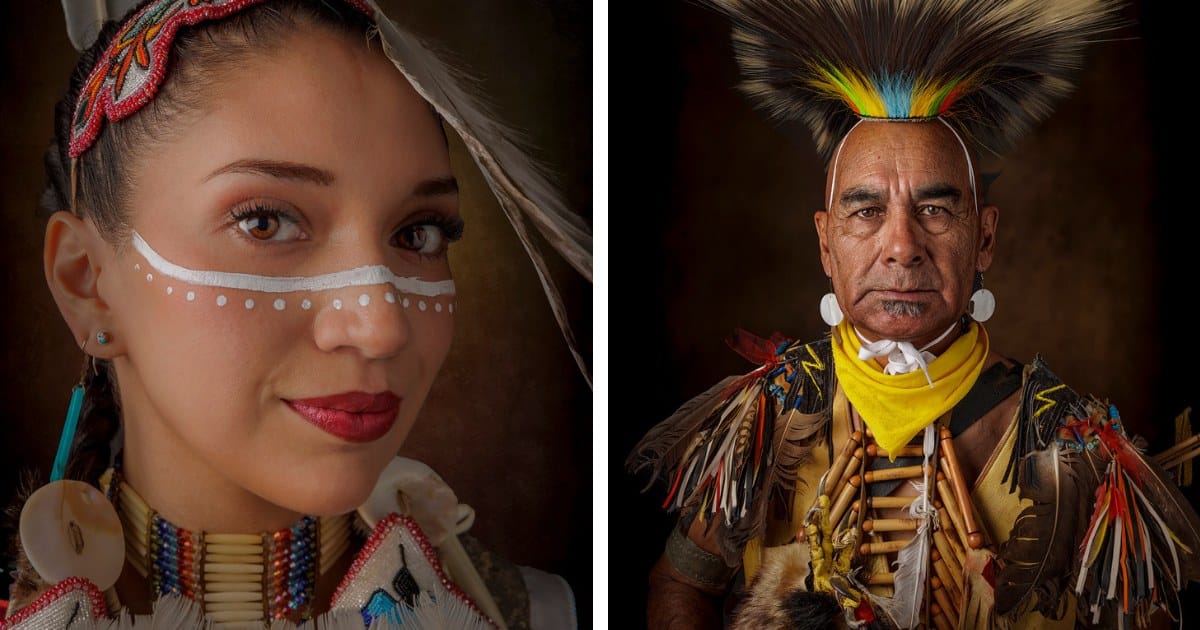

One day, a long time ago, I came to a fork in the road. I had to choose between my commitment to beauty and the landscape or follow an inclination towards the beauty in human beings. And they are beautiful. Every human being is a masterwork, a statement of IO’s (the Creator) intent through which he experiences him/herself. And, of late, I have found myself fascinated by what makes people the creatures they are.

And, how can I use the talents and skills acquired from 20 years of being mentored by one of New Zealand's most outstanding portrait photographers to answer another question:

Who are we really?

Let us see what and how that eventuates.

I sense it will be the same process for you because you are aware and have many questions left to answer.

I can't wait to see which path you decide to take.

If you have any questions you would like me to answer, please drop me a line and let me know what they are. Hopefully, I will get enough to share a few with you in the following newsletters.

Waiata Mou Te Ata-Poem For the Day

Ngaa Atewharowharo O Papatuuanuku, Te Tai Poutini, 2018 | Fujifilm X-H1, EF16-55/2.8

“Pick a flower on Earth and you move the farthest star.”

Sometimes the ideas for my poems come from moemoea (dreams), most of which come around 3 am.

A manu aute is a traditional Maaori kite.

A powhiri is a formal greeting when welcoming visitors onto a marae.

It is said the Rahiri, the Ngaapuhi son of Nukutawhiti and Puhi, when faced with the issue of allocating lands to his two sons, made a manu aute, then set it adrift on the wind. He told the elder son that where the kite landed would be the border of his lands. The other son could have what remained.

Manu Aute Kite Song.

And in the night

when the wind from the South is scudding north,

forming and kneading

dark beetlebrowed rollers of grimcloud

into slithering, elongated dourdough loaves,

I step outside and spread my wings

pinion my fingertips into the threads of the wind and clutch the fabric of the night,

allowing it to enfold, embrace and lift me high

above the dreamingmoon mountains

and blankfaced silveredmirror lakes,

past glowskeined glintrivers adrift in the night,

then reel me down the karanga's magnetic

call and summoning,

to alight alone

before a powhiri of shades and shadows past

on Puwheke.

Nine or a (baker’s) Dozen Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

EndPapers

Koorero Whakamutunga

Ki Roto-Uua, Fiordland 2018 | Fujifilm GFX 50r, GF 120/4 Macro

"Use what talents you possess; the woods would be very silent if no birds sang there except those that sang best."

And there we have it.

Breathing light Issue #80.

Two years ago, when I set out to create a newsletter worth reading, I never thought it would get this far.

80 issues. An average of 3000 words per issue adds up to around 240,000 words.

Whew!

Perhaps I should have written an extended novel set in Russia in times of war and peace.

Oh wait…

The Maaori name for the West Coast of the South Island is Te Tai Poutini. Very few people know or even ask for the back story of that name. Long before Maaori arrived in New Zealand, the Waitaha and Rapuwai people lived throughout the country in harmony with the peoples who had been there before them. And, at that time, no one knew about pounamu, the native jade/greenstone indigenous to Aotea Roa. Then, one night, the ariki (chief) Poutini, at the time living in the Far North, had a vision in which he was instructed to sail south and seek te kohatu o ngaa atua, the stone of the gods. He made his way south and eventually found it on the West Coast. He gathered up and brought it back north with him. Because it was such a valuable stone, there was soon a flourishing trade in it. Of course, they kept its location under wraps when Maaori arrived in the 13th century until a Waitaha kuia (wise elder woman) eventually told them where to find it.

The little maunga (mountain), the header image for this section, is known locally as The Monument; however, its Waitaha/Rapuwai name is Koromatua, which is rather difficult to translate. When I first arrived, it spoke to me, and each time I have returned from the north, it summons me to spend time with it. If you have ever listened to a Maaori recite their pepeha, or statement of whakapapa (genealogy), you will know that we refer to our home mountain, lake and river, for these are the places that have bred us and fed us, including our tupuna (ancestors) have preceded us. You can find mine here.

Since I have Rapuwai whakapapa, Koromatua is my maunga ki te tai tonga (mountain in the south). However, I also have whakapapa in the Far North, and there is another maunga which also forms part of my whakapapa, my Maaori heritage, descending from an ancestor who arrived with the great Polynesian navigator Kupe around 875. And, since I have whakapapa ki Te Tai Tokerau (the Far North), I also have a foot up there.

And that maunga is calling me back.

All going well, I am returning to the North for Christmas to stand inside ngaa poupou o Ngaapuhi (the pillars of Ngapuhi) in the house of my ancestors.

So, Breathing Light is taking a break. There won't be one next Sunday as I will be busy this coming week preparing to fly out and spend Christmas with Sarah.

There is a myth about swan songs: a swan only cries before dying. Of course, this is not true. Swans have a range of cries and do this throughout their lives. However, there is something about the graceful way a swan bends its neck that can be seen as a metaphor for bowing to the inevitable. Endings and beginnings. One must close before a new one opens, and we can walk through it.

Regular service will resume sometime after the New Year.

If you need a Breathing light fix, you can trawl back through the other 79 issues. Just follow the link at the foot of this email.

Wherever you live, may the coming weeks and festive season bring you love, wisdom, truth and peace, the only things we can ask of our Creator.

As always, let us walk gently upon our Mother and be kind to each other.

He mihi arohaa nunui ki a koutou.

Much love to you all,

Tony/Te Kupenga a Taramainuku