In this Issue

1. Taku Mahi Toi o Te wiki-My Artwork of the Week

2. Korero Timatanga-Frontispiece

3. Letters to my Friends-Letter to Sarah: On Documenting The Space Between

4. Waiata mou te Ata-Poem for the day

5. Nine or Ten Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

6. Koorero Whakamutunga-Endpapers

My Artwork of the Week

Taku Mahi Toi o Te Wiki

Kokerboom, Namakwaland, South Africa 2006 | Canon 1Ds Mk II, EF16-35/2.8L

"We need to find God, and he cannot be found in noise and restlessness. God is the friend of silence. See how nature - trees, flowers, grass- grows in silence; see the stars, the moon and the sun, how they move in silence... We need silence to be able to touch souls."

In 2006, due to drastically changed personal circumstances, I decided to quit my day job and head out into an uncertain future to try and make my living as a full-time photographer. I had time on my hands and a little money, and, me being me, I decided to follow my heart and see where the road led.

For four years, I worked on and off as an assistant to the great Canadian photographer Freeman Patterson. Not long after I left a secure and safe job as a schoolteacher, he reached out to me and offered me the chance to teach with him during the flower season in NAmakwalan, South Africa. Until then, the only time I had spent out of our Aotea Roa New Zealand was a couple of trips across the Tasman Sea to Australia. I would have to fly halfway around the world for five weeks or so, and I had no idea what I was doing.

When I went to the bank to sort out my finances, the lovely South African consultant reeled back in horror.

"You must be joking. Why on earth would you want to go there? You will almost certainly be murdered. "

I blinked. What on earth was I letting myself in for?

However, being the stubborn, cantankerous individual I am, I went anyway.

When I stumbled out of the airport in Johannesburg and smelt the wood smoke from all the cooking fires hanging in the yellow air of a South African evening, I fell madly in love with Mother Africa. For reasons I could not explain, I had a strong sense of going home and back to Source.

On the plane down to Cape Town, I sat beside an executive from Telkom, the South African communications company. We started a lovely conversation about photography. Then it happened again.

"Where are you staying?" He asked.

I told him.

"How are you going to get there?"

"Oh, I suppose I will get a taxi."

Again, that horrified look.

"You must never take any taxi in South Africa. Because you are white, you will be robbed and murdered."

I was beginning to doubt my decision to go to South Africa.

The next day, I caught a bus up to Namakwaland.

And then I began to look around myself at the strange landscape and the even stranger plants.

Late one afternoon, we were travelling back from Springbok to Kamieskroon. The light had that lovely orange-red glow that paints the landscape at that time of day, the warm, inviting luminosity that make you want to sit outside on the stoep (patio) with a glass of red wine and celebrate the joy of being alive.

In front of us was one of those strange trees that littered the landscape.

"What on earth is that," I asked. "

"Oh, that," replied my new friend, Reg, "is a kokerboom, a quiver tree."

He stopped the car, and we walked across to it. Having never seen one before, I found its leathery trunk quite alien and the spiky leaves bizarre.

He explained how the tree stores water in its trunk and how the local bushmen use it to hydrate themselves when travelling across a landscape that rarely receives any rainfall.

He showed me how the bark on the sunny side of the tree was warm to the touch, and yet the opposite side was quite extraordinary. It was an eerie experience to put both hands on either side of the tree and have one warm and the other cold.

In many ways, the kokerboom is a living metaphor for Africa.

One evening, at a braai (barbecue), one of the locals (who were somewhat amused to have a genuine Kiwi in their midst) asked me a question:

"so what do you think of Africa?"

I thought about it for a moment.

"Well, in many ways, it is like walking along a railway line with one of my feet on one rail and the other on its partner. Whatever you say about Africa, the opposite is equally true."

He looked at me for a moment, then nodded approvingly.

"Yes, you get it. You understand Africa".

Larger sizes on request.

Open Edition A2

$NZ 800 (print only).

Frontispiece

Koorero Timatanga

Autumn into Winter, Hanmer Springs 2011 | Sony A900, Sony 24-70/2.8 ZA

“The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched - they must be felt with the heart.”

Atamaarie e te whaanau:

Good morning, everybody,

Firstly, I would love to welcome you new subscribers from different parts of the planet, especially Canada. It is lovely to have you on board, and hopefully, you will find each weekly offering helpful and joyous. As always, I welcome suggestions about how to make this e-zine better. If you have the time, I would love you to drop me a line, let me know where you are, and, if you are a photographer, perhaps share a picture.

One of the most fun things about writing Breathing Light is going off and looking for suggestions for the Fevered Mind Links, then assembling them into a collection that will hopefully meet all of your needs (well, perhaps some of them!). As I was trawling through the Internet this week, I found a link to a page that celebrates "natural" photography, which celebrates in-the-camera capture and minimal manipulation.

To put this in context, we are all aware of the power of AI to change our pictures. We can swap backgrounds and subjects, extend the canvas and even generate images from text. There is no question in my mind that this will only "improve" and further develop. It will reach a point where photographic reality will always be in question. That said, in the early days of Photoshop, people worried about the application's ability to transform reality. Photoshop move the goalposts further out, yet today, we take it for granted and do not get particularly troubled.

However, I am not so sure about AI. Frankly, for now, I am uneasy. I have a confession: I have used AI to improve the composition of my photographs by extending the background. I have used it to write SEO and Meta for my web pages because it does an outstanding job of it, far better than I ever could. However, I draw the line at dropping artificial skies into my landscapes. Yes, I use software that enables me to enhance it, but I have no problems with that.

Interestingly, in the links below, you will find an interview with the great linguist Noam Chomsky, who has thoughts on the matter. We will have to think about this for ourselves and choose where we stand. What do you think? Let me know.

As with all movements, there is the inevitable pushback. Now, there are competitions for photographs that are mainly in camera and promote a documentary view of the world, even though they may be slightly enhanced (all digital photography is enhanced!).

I have a friend who won a photography competition where each entrant had to supply the original RAW file. No postproduction was permitted. Having seen her entry, I was gobsmacked. It needed no enhancement at all. It was a perfect document, yet full of emotion and meaning.

Another example of this pushback is the sudden popularity of film. Kodak is busily hiring technicians to help them keep up with the demand; Fujifilm makes an enormous amount of money each year from their Instax product line, essentially Polaroid revisited. You compose the photograph, push the button, and, after a short interval, out pops a finished print. It is particularly popular with millennials, who are busy buying up every second-hand film camera on the market, often for ridiculous prices. I read somewhere that Asahi Pentax is working on releasing a film camera, the first in probably 25 years. A new camera company, Mint, have begun producing handmade old-school twin-lens reflex and foldout bellows cameras with beautiful glass lenses engineered to take Instax film. I am sure the great artist David Hockney, who went there with his Joiner series in the 1980s, is laughing his head off.

There is a lovely Maori whakatauki which goes like this:

Kia mataarata ki uta

Kia mataarata ki tai

the tide flows in; the tide flows out

Perhaps we are watching photographic (re)birth pains again.

Photographer's Corner

Letters to My Friends

Letter to Sarah:

On Documenting the Space Between

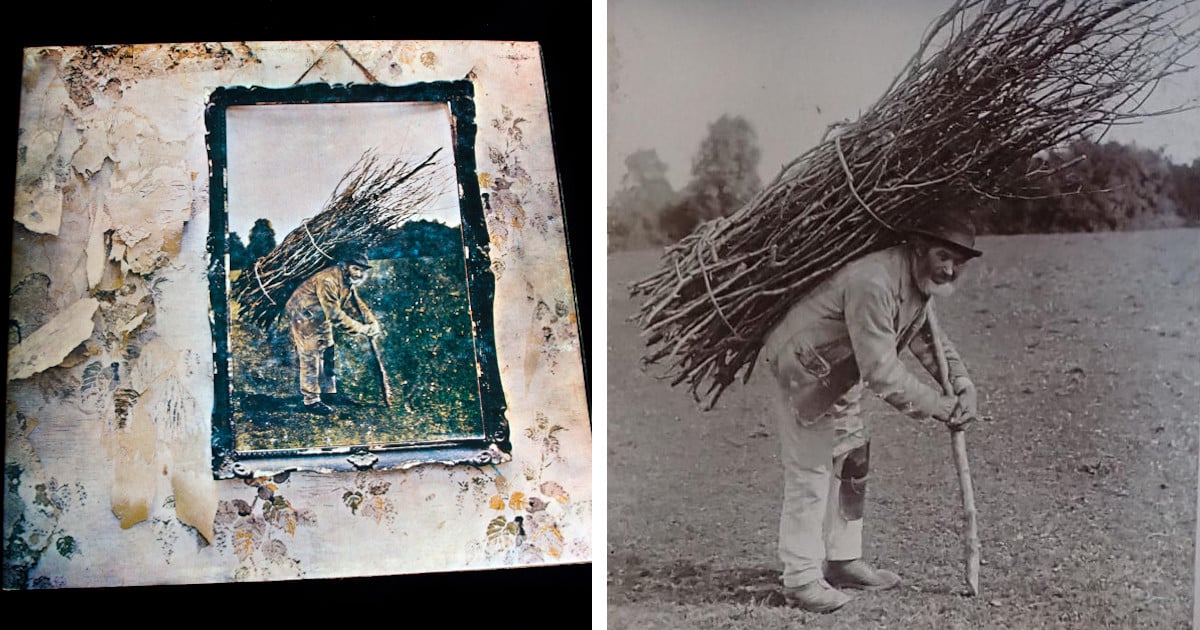

Anna Tait-Jamieson on her wedding day | Photo: Sarah Willacy, from a film negative

"Photography is a way of feeling, of touching, of loving. What you have caught on film is captured forever... it remembers little things, long after you have forgotten everything."

Letters to My Friends

Letter to Sarah:

On Documenting the Space Between

Dear Sarah:

It is lovely to see your passion for photography rekindling.

I enjoy our robust conversations, where you take a position and hold to it. Irresistible force meets immovable object.

For some time now, we have tossed around the words we use to describe the act of photography. So many people use the word "take" without really thinking about it and completely unaware that that particular verb came into our lexicon as a result of an advertising slogan put out by the Eastman Kodak company back in the late 1800s when they were promoting the radically new Box Brownie, the first camera that enabled the man in the street to make his own photographs. (You will note I use the word "make"). The slogan was:

"you take the photographs; we do the rest." This is because very few people had the knowledge, expertise, and technology to develop their film photographs, so Kodak took care of that for them. You would take your camera into the shop/chemist, and he would swap the film over for you, then go away and process it and make prints. Too easy.

Then, the other day, you pointed out that the words we use to describe the act of photography are hunting words. We use words like shoot, capture and take. All of these are words that describe photography as an alternative to going out hunting live animals. There is a great deal of truth in this, and having watched other photographers at work, I cannot help but agree. Perhaps we like to think of ourselves as great hunters in search of moments to appropriate.

Interestingly, the one photographer I knew who completely understood this was the late Gordon Roberts, who spent much of his early life as a deer Culler, a person employed by the New Zealand government to kill as many deer as possible from the enormous herds ravaging the New Zealand landscape. The hunters were paid by the tail, in other words, by the number of deer they shot. In later life, Gordon found work with the New Zealand Forest Service, where I met him as one of his employees. He was the person who lit the photography fire within me, and we became firm friends over the years. Occasionally, he would turn up, and we would discuss photography. By then, he had given up shooting and swapped his rifles for a camera. Gordon, who was so fit he could run up a mountain, shoot a deer, and be back by breakfast, used those same skills to go out and photograph wild game animals in the mountains. He eventually produced a wonderful book, Game Animals of New Zealand, with glorious photographs of chamois, tahr, and deer. You can still pick up a copy on the second-hand shelves here and there. It is a genuinely remarkable opus. I have included a portrait of him I made at the bottom of this letter.

Then, the other day, you observed that in so many ways, the photographs we make are of the relationship between photographer and subject rather than the subject before us.

I cannot agree more. Every photograph we make is a statement about how we feel about what is in front of us. In other words, it is a statement of the relationship between the subject and the photographer. So often, it seems to me, we are so focused on the capture/shot that we are oblivious to the intrinsic nature of our subject and yet so determined to impose ourselves upon it that we are utterly blind to who/what it truly is.

The great photographer Minor White, a devotee of the Russian mystic Gurdjieff, had one of his students ask him one day:

"Mr White. When will I know the right time to make the exposure?"

White's reply was this:

"be still within yourself until the object of your interest affirms your presence."

How much more meaningful would our photographs be if we took the time to understand and listen to our subject? Note that this applies equally to the land as it does to making pictures of people.

And why do we photograph anyway? What makes photography the second most popular pastime in the world (do not ask!)? And no, it is not golf…

The great New York art critic, the late Susan Sontag, puts it this way:

"The camera makes everyone a tourist in other people's reality, and eventually in one's own."

And yet…

And yet…

I have long felt that photography is much more than that. We like to think we have made a likeness of what was before us, of a place, event or moment. I believe, however, the photograph is not just a statement about place and time. It gently wraps itself around the space between the photographer and the subject. In other words, it documents neither the subject nor the photographer but what is happening between them.

Thank you so much for sending me that photograph of your sister Anna on her wedding day. It is a beautiful photograph of what was obviously a wonderful day and a lovely document of a joyous moment. However, and perhaps because I know the back story, what truly stands out here is your love for her. It is a beautiful statement of your relationship, in other words, of the space between you.

Perhaps the finest photographs are the ones of the Space Between, of the relationship between photographer and subject.

As Sontag puts it:

Any photograph has multiple meanings: indeed, to see something in the form of a photograph is to encounter a potential object of fascination. The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say: "There is the surface. Now think – or rather feel, intuit – what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.'

Perhaps the most remarkable photographs are the ones that reach below the surface and explore the space between.

If you have any questions you would like me to answer, please drop me a line and let me know what they are. Hopefully, I will get enough to share a few with you in the following newsletters.

Gordon Roberts at Mt. White Station, Canterbury 2006 | Canon 1Ds Mk II, EF 24-70/2.8L

Waiata Mou Te Ata-Poem For the Day

Trees in Snow, Hanmer Springs, 2011 | Sony A-900, Sony 75-300 SSM

“Even after all this time, the sun never says to the earth, 'You owe me.' Look what happens with a love like that. It lights the whole sky.”

Sometimes, the idea for a poem will come from simple things, like the soft kiss of wind on my cheek, the movement of clouds in the sky or perhaps even the song of a bird nearby.

At other times, inspiration comes from a picture I made many years ago, which seems to be putting up its hand and asking for acknowledgement and homage in words.

Twelve years ago, the winter snows came to Hanmer Springs, and excitedly, I set off through the snowdrifts in search of homages to winter. On a back road, I stopped, entranced by a simple row of trees protruding from the snow.

I have always loved this photograph. Somehow, it sums up for me the essence of winter.

Warp and Weft of Winter song.

The Weaver of Winter Quilts has come

sere and austere

with dour, downturned mouth and bluebleak cloudstreaked face

and icecrystal sapphireshard eyes,

casting a woven blanket of white

across an open upturnedmouth land.

She takes a deep breath, sucks in her cheeks

and blows away the last rosy remnants of autumn.

Then, whipping the obedient winterwind into line

she shuttles layers of snow back and forth

in deft wefts of white and ashen grimgrey,

until only shivering shards of bony, leafless trees

with quivering cowering branches

scratch protesting shards of charcoal

On the scarified wall of the day.

Nine or Ten Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

EndPapers

Koorero Whakamutunga

Westport, Aotea Roa New Zealand 2006 | Canon 1Ds Mk II, EF16-35/2.8L

"Prejudice is a great time saver. You can form opinions without having to get the facts."

Ebel and Michelle, who call by from time to time to mow my lawns, had not been for a while. I knew they were busy trying to keep up with all their customers' needs. It is, after all, late spring, and the grass in the district has been growing prolifically.

However, it was not so much a matter of standing on the grass as wading through it. The lawn was full of seed heads 30 cm high and tiny rings of daisies, beautiful in themselves, yet it made the property look messy.

I was wondering how to let him know without appearing to grump. Ebel is a lovely man with a massive sense of humour, and it would have been easy to complain.

I jumped onto Messenger and sent him a YouTube link to "Welcome to the Jungle" by Guns' n Roses.

Message received, he replied, with lots of laugh emojis. A week later, when he still had not been, I sent a picture of the cover of The Jungle Book—more laugh emojis. We will be there just after lunch.

After he had been, the blackbirds arrived and darted about, busily feeding on the worms just below the surface. With a beak full of squirming worms, one of them focused one yellow-rimmed eye upon me.

"What the hell are you looking at? It's about bloody time you had the lawn mown!"

It fascinated me how it could see those worms writhing below the surface. Its eyesight must be phenomenal. Then, the thought occurred to me that I might be crushing small creatures beneath my feet every morning when I go outside to stand on the grass. Perhaps I should be more aware of the tiny lives beneath my feet.

Perhaps I should be more sensitive to the minutiae of nature.

Imagine, if we all took that approach, we would do a better job of our role as kaitiaki of Papatuuaanuku, our Mother the Earth.

May the coming week bring you love, wisdom, truth and peace, the only things we can ask of our Creator.

I wish you all love, truth, wisdom and peace.

As always, let us walk gently upon our Mother and be kind to each other.

He mihi arohaa nunui ki a koutou katoa

Much love to you all,

Tony/Te Kupenga a Taramainuku

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/candied_fruit_peel-5830e2e33df78c6f6ad4f50d.jpg)