- Breathing Light

- Posts

- Breathing Light Issue #58

Breathing Light Issue #58

On the wonder of breathing invisible Light

In this Issue

1. Taku Mahi Toi o Te wiki-My Image of the Week

2. Korero Timatanga-Frontispiece

3. Photographer's Corner-On the wonder of breathing invisible light

4. Waiata mou te Ata-Poem for the day

5. Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

6. Koorero Whakamutunga-Endpapers

My Image of the Week

Taku Mahi Toi O te Wiki

Secret Tarn, Milford Road, Fiordland 2019 | Fujifilm X-Pro1, XF 18-135/3.5-5.6

" Those who throw dust at the sun, the dust falls in their own eyes."

For as long as I've been travelling the black ribbon of road that dances through the forest to Piopiotahi/Milford Sound, its song has entranced me.

Over the five years I've been driving along it, I've realised that I've been a spectator invited to be a participant, to lower myself beneath its surface and wander its River of intention. How wonderful is that?

And, as I've bowed to its wonder and wisdom, it has picked at the encrusted corners of my preconception, prised open the shell of my ego and showed me its beautiful little corners. The forest is far more than an arrangement of trees, rivers and slab-sided mountain gods with grim expressions. Within its body live the seeds of times past, present, and to come.

One day as I was driving, a gentle cough plucked at the corner of my vision. I quickly checked my rear vision mirror, afraid that a 13-tonne bus desperate to get to Milford would be up my tail, and pulled over as far as possible to the left without making a departure from the swampy ground difficult. In a small clearing was a tarn surrounded by trees. At its head was a single tree, looking for all the world like a sentinel guarding the entrance to a deep and sacred place.

I knew it was.

I got out, took my camera and padded through the heavy dew-bowed grass to the tarn's edge. I took my tripod and did the best I could. None of the images resonated in any way. Sometimes your first introduction to somewhere sacred and special is less than optimum. In some ways, when that happens, I know that this relationship has potential. I have to keep returning until it decides to show me what is to be seen.

I repeatedly returned, each time with the same result, a sense that I was knocking on the door of the obvious, that there was a mystery here that I wasn't yet ready to encounter. Ah well.

I've often wondered why more people don't stop and explore it. It is because it is hidden in plain sight at the end of a long straight into and out of the forest. Drivers rushing to be on time for the cruise on the fjord are focusing on the road, while drivers returning home have showers, food and drinks on their minds and are putting their foot down. Somehow the thought of a place so sacred being ignored by consumer tourists is fine by me.

Their loss.

One day I was returning from Piopiotahi. It was mid to late afternoon, a sunny day with shadows too strong to make photographs in the forest worthwhile. As I passed the tarn, a voice whispered in my ear. I did a U-turn as soon as safely possible and quietly returned.

I'd spent the day with a camera I had converted to shoot full-spectrum Infrared some years ago. I was exploring the idea of how the world must look to animals that see in Infrared and insects that tend to see in ultraviolet. What must they see when they move within the body of Te Taiao, the natural world? And how could I reflect that in the pictures I made?

I wandered across to the edge of the tarn and stood there, basking in the late afternoon sun and the peaceful glory of a perfect day. The late light made the Sentinel Tree and grasses beside the water glow.

Somehow the labels fell away, and all I felt was the old and sacred energy of a place which didn't give itself away lightly.

Koorereo Timatanga

Frontispiece

Green tomatoes in sunlight, Te Anau 2023 | Fujifilm X-Pro1, XF 18-135/3.5-5.6

“I did not wish to take a cabin passage, but rather to go before the mast and on the deck of the world, for there I could best see the moonlight amid the mountains. I do not wish to go below now.”

Atamaarie e te whaanau:

Good morning everybody.

Each day I like to go out and tend my tomato plants. I feed them, water them, talk to them, and watch them busily produce fruit. I marvel at how the dangling flowers suddenly seem to morph into small green balls overnight. I've had a lot of advice and encouragement from friends who are wise in the ways of tomatoes and do unmentionable things to them to make sure they are on the right track. That is a beautiful thing about gardeners. So many of them are apparent experts, and my tomatoes do not have a chance of being unruly or unproductive.

However, all these fabulous green globes are stubbornly refusing to change colour. Down here in Fiordland, the growing season is short, and although we have had one of the warmest, driest summers in living memory, all things must pass, and I suspect I may have missed the cut. So, with perhaps a month of warm weather left, I may be investigating making green tomato chutney.

Indeed, the white butterflies, who gaily stitch mocking threads of sunlight in the yellowing autumn air, are winning the battle between them and me in my attempts to grow Chinese cabbage.

I suspect I will be growing them in my supermarket shopping bag. I feel somewhat like the man who heads out proudly on a fishing trip, promising his wife he will bring back fish for dinner. Then, when he returns in the evening, he boasts of his catch-until she spots the supermarket receipt in his pocket.

I admire people who speak the language of vegetables and can entice them into growth and being productive.

Perhaps we should issue awards and medals to people who grow food (especially tomatoes) instead of retired politicians or successful capitalists.

Imagine the Queen's Birthday honours list:

Sir Tom Bombadil for services to zucchini growing and Dame Vivienne Smith for services to the preservation of heritage seeds.

Looking for something to write about this week, I stared at the tomatoes and wondered how I might photograph them. Then I thought about how I see tomatoes and how insects and some animals view the world. For example, a couple of species see the world in Infrared, while many insects use the ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Then I remembered my (limited) journey with infrared film and voilà, the topic for this week's offering.

Photographer's Corner

On the wonder of breathing invisible light

As I were an iris 2021 | Fujifilm X-Pro1, XF 18-135/3.5-5.6

“Maybe it’s impossible

for poets to hide

the abundance of moons inside

when their heart is carved

from the clouds of a sunrise.”

A long time ago, in a decade far, far away, when film ruled and digital photography was little more than a concept (if that), there was a vast range of film emulsions available to the photographer. One of these was infrared film, initially developed by Kodak Eastman in the 1930s and mainly for the benefit of scientists and other researchers.

As time went by, other uses were found for it. False colour Infrared came a bit later and, like so many modern technological innovations, it was born of military necessity.

By the Second World War, the art of camouflage had become so sophisticated that it was hard to tell where enemy battalions were located. The film was based on the principle that living sunlit foliage emits enormous amounts of infrared radiation. This renders as a high tone (sic: white) on black and white infrared film and a purple colour on Ektachrome false colour Infrared. Diseased or dead foliage renders as a much lower tone. Standard aerial photographs of the camouflaged area might show no difference between the hidden area and the surrounding forest. However, the pictures would tell a different story. The US military used this knowledge to telling effect in Vietnam in their bombing campaigns against the North Vietnamese, who were masters of the art of camouflage.

Later it became a product much used by fine art photographers like Minor White, who employed it to help express his view of the world.

When I was using it, I was a Kodak professional mentor and thus had a lot to do with our New Zealand Kodak rep, an ex-Air Force-trained photographer. One day he told me a wonderful story about how he had been employed as an aerial photographer not long after leaving the Air Force. Part of his work was to fly grid patterns over the pine forests around Taupo and Rotorua in the central North Island. Unhealthy plantations would render on film a much darker tone and thus be targeted for treatment. One day, after flying over the forests around Rotorua, they noticed small patches in the forest were much brighter in tone and not the dour middle grey of pine needles. Instead, it was the signature of much larger leaves and actively-growing plants. At first, they weren't sure what to make of it, and then the penny dropped. They made a duplicate set of prints and dropped them around at the local police station. I'm sure the local growers were stunned at being found out.

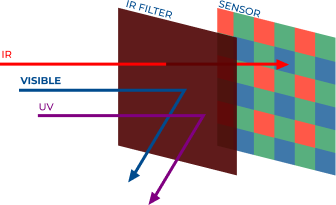

A little science is needed to understand infrared film and how you can use it. Our human eye sees a very limited part of the electromagnetic spectrum, between roughly 300 nm (blue) and 630 nm (red). Below 300 nm is ultraviolet, and above 630 nm is infrared. Our human eye cannot see either of those, but tell that to many insects whose vision is responsive to ultraviolet and some mammals whose vision/seeing responds to Infrared wavelengths.

Using infrared film was tricky at the best of times (you can't buy it anymore). You had to load the film in total darkness, get it from the camera to the developing tank in complete darkness, and adjust your point of focus manually. In addition, most old-school prime lenses had a small red mark on the lens barrel. After focusing by eye, you would shift the focus point opposite the little red mark. This was because infrared light focused at a slightly greater distance than visible wavelengths.

Most near-infrared light occurs in a band between approximately 650 nm and 1500 nm. So to get the most out of it was necessary to block off the visible part of the spectrum and below by using heavy filters, which transmitted only infrared light. Also, the film lacked an anti-inhalation layer (put on most films to prevent light from bouncing back and double-exposing the film). This meant that highlights often flared badly, like having the front of the lens coated in Vaseline (a firm soft-focus favourite of the early black-and-white cinematographers).

And so time went by, digital photography came, and infrared film photography vanished from the market.

However, did you know that your digital camera, especially if it is mirrorless, can happily see from near ultraviolet to well into the infrared spectrum? Here is why.

Digital sensors on most cameras can see from approximately 290 nm to roughly 1400 (depending upon the manufacturer). Almost all digital cameras are fitted with an IR cut filter, which blocks off the wavelengths above the end of the visible spectrum. The manufacturers want to give you an experience and result as close as possible to the way your human eye sees it (or they think you see it). Remove that filter, and your sensor can now see a much greater range of wavelengths, which you can modify and adjust using filters. This is known as full-spectrum infrared photography.

To be able to do this, you need to have your camera converted or, better still, have a second body you can have converted. That camera will then be able to see infrared. Conversion isn't costly, but you need to realise that if the conversion is done, your camera will be limited to only that type of photography.

My dear friend Ray Cho and his wife were out from Taiwan visiting. He let me play with his camera and, when I expressed an interest, asked me if I had a camera I didn't need any more. My eye fell upon my Fujifilm X-Pro 1, languishing in a corner unused. Why not that one? I asked. He took it away with him, and after a few weeks, it returned, its IR cut filter replaced by a piece of plain glass and several screw-on filters for me to choose what effect I needed.

I suggest that those of you interested in this type of photography might want to have a look at the last link in the Fevered Mind links below.

However, the question remains as to why you would want to get into this particular corner of photography. There is always the joy of doing something different and producing results that are hard to replicate, even with all the cool photoshop plug-ins and tools. You can get partway, thereby messing around with the channel mixer, but it is not the same.

What still fascinates me and makes it something I want to use is that it enables me to see beyond the limits of my vision and perhaps look at the world through the eyes of other creatures.

Waiata Mou Te Ata-Poem For the Day

Poppies, Te Anau 2021 | Fujifilm X-Pro1, XF 18-135/3.5-5.6

“The moth prefers the moon and detests the sun, while the butterfly loves the sun and hides from the moon. Every living creature responds to light. But depending on the amount of light you have inside, determines which lamp in the sky your heart will swoon.”

Somebody recently asked me how I go about writing my poetry. As often as not, the words come at dawn or thereabouts. I will go outside in the space between night and day and stand barefoot on the grass, listening to what it has to tell me, what the stars above me are trying to get through to me and, best of all, what stories the wind has carried across the night for me to learn. Then I will open myself up to what want to be pinned in place. I allow the poems to find their way through me and onto my phone screen. As often as not, the endpoint will be tangential to where I began. I never saw that coming…

I have a folder where I store all my waiata, and when I looked to save the document, I realised just how many of them are about the moon, moths and the energies of the night.

I wonder what that says about me.

Moon Mothmaiden Song

The mesmerised moon moth-maidens have been at work all night,

carving meandering veins of spidery light

with delicate brushwinged scalpels caressing

the soft palpitating onyx of the night

Slicing away glowing spirals of memory

and pinning them to the dark.

Drawing down dripping silver strands

from their goddess mother, the round-faced moon

they paint the song of autumn on yellowing, curling paper leaves

slowly fanning themselves with shadow.

And in the morning, at the last of the night

when I step outside and stand barefoot on the grass,

to fingerfollow a wandering procession of stars

splitting and peeling apart the overarching skin of the night,

the soft skirl of decay and rotted summer

lingering pale, pungent and perfumed

paints itself on the cooling ashes of the night.

Fevered Mind Links (to make your Sunday morning coffee go cold)

EndPapers

Koorero Whakamutunga

Impression, Te Anau 2021 | Fujifilm X-Pro1, XF 18-135/3.5-5.6

“In old age gravity gets stronger, time goes faster and the temperatures get colder.”

On the song of the galaxy

I suspect we each have our own favourite time of day. For some of us, it is the evening, after the dust of the day is settled, when the world is quietened (or so it would seem), and we can begin to float and drift on the ocean of the night. However, our lifestyle may allow us to compensate by sleeping in until “that busy old Foole, unruly Sonne” prizes our curtains apart and wakes us to another day.

We are owls.

For others of us, the time we most treasure is daybreak. We like to rise before the sun has come over the horizon (a thing easier to do these days as winter approaches and the night's length) and float in the space between night and day.

We are larks.

When I stepped off the edge of my patio to stand on the dew-laden grass, I looked up at the sky and saw for the first time in quite some time that the Milky Way had reappeared. Somehow it had pushed the moon into the background, and above me, in all its magnificence, the arc of stars swept across from north to south. The photographer in me contemplated racing to our local lookout to stand like stout Cortez and survey some celestial Darien.

Then I came to my senses.

Sometimes the wonder of a moment is so great that there is no need to race off and busy ourselves trying to consume it with the camera.

Sometimes being present at and to the wonder of a moment is enough.

Put another way; perhaps it is better to watch a train pass through the station than to be on it.

As always, walk gently upon our Mother and be kind to each other.

He mihi arohaa nunui ki a koutou katoa

Much love to you all,

Tony.

Reply